Title:

Panel 2: Toyah Defined

Collection:

Little Paint Collection

Object ID:

CAS.2013.07.PIC.83

VE Exhibit Label 1:

What does "Toyah" mean?

The designation "Toyah" refers to a unique set of tools and

techniques, a "technocomplex,” that was used by several Native American groups between approximately A.D. 1300 and 1650. The findings at the Little Paint site support a model of small parties using the toolkit on a seasonal basis during long—range hunting forays. Evidence suggests bison, which moved south during the late fall and early winter, were the primary prey, although deer and antelope were also common targets, along with other locally occuring resources.

The designation "Toyah" refers to a unique set of tools and

techniques, a "technocomplex,” that was used by several Native American groups between approximately A.D. 1300 and 1650. The findings at the Little Paint site support a model of small parties using the toolkit on a seasonal basis during long—range hunting forays. Evidence suggests bison, which moved south during the late fall and early winter, were the primary prey, although deer and antelope were also common targets, along with other locally occuring resources.

VE Exhibit Label 2:

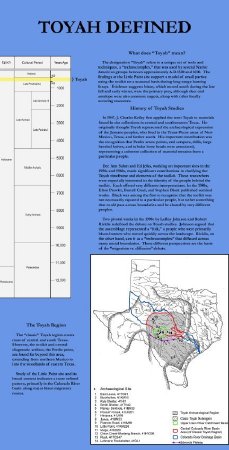

The Toyah Region

The "classic" Toyah region covers most of Central and South Texas. However, the toolkit and central diagnostic artifact, the Perdiz point, are found far beyond this area, extending from Northern Mexico into the woodlands of eastern Texas.

Study of the Little Paint site and its broad context indicates a more refined pattern, primarily in the Colorado River basin along major bison migratory routes.

The "classic" Toyah region covers most of Central and South Texas. However, the toolkit and central diagnostic artifact, the Perdiz point, are found far beyond this area, extending from Northern Mexico into the woodlands of eastern Texas.

Study of the Little Paint site and its broad context indicates a more refined pattern, primarily in the Colorado River basin along major bison migratory routes.

VE Exhibit Label 3:

History of Toyah Studies

In 1947, J. Charles Kelley first applied the term Toyah to materials found in site collections in Central and Southwestern Texas. He originally thought Toyah represented the archaeological expression of the Jumano peoples, who lived in the Trans—Pecos areas of New Mexico, Texas, and farther south. His important contribution was the recognition that Perdiz arrow points, end scrapers, drills, large beveled knives, and tubular bone beads were associated, representing a coherent collection of material remains from a particular people.

Dee Ann Suhm and Ed Jelks, working on important sites in the 1950s and 1960s, made significant contributions in clarifying the Toyah timeframe and elements of the toolkit. These researchers were especially interested in the identity of the people behind the toolkit. Each offered very different interpretations. In the 1980s, Elton Prewitt, Darrell Creel, and Stephen Black published seminal works. Black was among the first to recognize that the toolkit was not necessarily equated to a particular people, but rather something that could pass across boundaries and be shared by very different peoples.

Two pivotal works in the 1990s by LeRoy Johnson and Robert Ricklis redefined the debate on Toyah studies. Johnson argued that the assemblage represented a "folk," a people who were primarily bison—hunters who moved quickly across the landscape. Ricklis, on the other hand, saw it as a "technocomplex" that diffused across many social boundaries. These different perspectives are the basis of the "migration vs. diffusion" debate.

In 1947, J. Charles Kelley first applied the term Toyah to materials found in site collections in Central and Southwestern Texas. He originally thought Toyah represented the archaeological expression of the Jumano peoples, who lived in the Trans—Pecos areas of New Mexico, Texas, and farther south. His important contribution was the recognition that Perdiz arrow points, end scrapers, drills, large beveled knives, and tubular bone beads were associated, representing a coherent collection of material remains from a particular people.

Dee Ann Suhm and Ed Jelks, working on important sites in the 1950s and 1960s, made significant contributions in clarifying the Toyah timeframe and elements of the toolkit. These researchers were especially interested in the identity of the people behind the toolkit. Each offered very different interpretations. In the 1980s, Elton Prewitt, Darrell Creel, and Stephen Black published seminal works. Black was among the first to recognize that the toolkit was not necessarily equated to a particular people, but rather something that could pass across boundaries and be shared by very different peoples.

Two pivotal works in the 1990s by LeRoy Johnson and Robert Ricklis redefined the debate on Toyah studies. Johnson argued that the assemblage represented a "folk," a people who were primarily bison—hunters who moved quickly across the landscape. Ricklis, on the other hand, saw it as a "technocomplex" that diffused across many social boundaries. These different perspectives are the basis of the "migration vs. diffusion" debate.